Open House, Open Possibilities

by Santy Calalay

March 12, 2020. Toff de Venecia, Congressman and VP of PhilStage (the umbrella organization for all performing arts companies), had just finished rehearsals for REP’s Carousel. He was all set to watch a preview of REP’s Anna in the Tropics. That evening, President Duterte had just announced the nation would be undergoing lockdown due to an emerging COVID-19 pandemic. This was to go into effect that weekend. Uncertainty about the future was in the air. Toff bumped into Audie Gemora, President of PhilStage, who was also at the preview. They both knew they had to answer the question – what will happen to the industry’s freelancers?

“Freelancers are in a policy limbo,” worried Toff. “They don’t get benefits afforded to formal workers, unlike indigents or those in sectors that would receive assistance from the Department of Social Welfare.” The pandemic revealed the vulnerability of people working in the creative industries such as film, TV, music, performing arts, fashion, etc. Known as an “underground economy,” many freelancers live paycheck to paycheck from one gig to the other. Thus the government was not cognizant of the creative industry’s contribution to nation building and the GDP. With the lockdown in place, all shows were postponed or completely shut down. Free-lancers found themselves jobless, unable to make a living.

Fast forward a few weeks later, the lockdown was extended. Would the government provide assistance? What would the theater industry do to help their displaced workers? Other industries had already started their own initiatives – Lock-down Cinema emerged to raise money for people in the film industry by monetizing short films. Bayanihan Musikahan did online concerts to help the urban poor and frontline workers through the pandemic.

The initiative for the performing arts started with Ticket2Me, an online ticketing platform for events and ticket buyers. Ticket2Me contacted Dingdong Rosales of SPIT (Silly People’s Improv Theater) about what they could do to raise funds for displaced workers. SPIT then contacted Jenny Jamora of TAG (Theater Actors Guild) who brought in AWPI (Artist Welfare Project Inc.) and PhilStage. With the core group in place, the brainstorming began.

Two conditions were agreed on by everyone. The fundraiser had to be LIVE and it had to be FREE. Even though the stage would be different, it was still theater. It still had to to be performed to an audience. Anyone would be able to access the shows, and donations would be encouraged. The idea was to simulate the experience of buying a ticket (through Ticket2Me) and watching a show. The name Open House was decided on. “Even if all shows were closed, the HOUSE would be OPEN for performances,” Audie explained.

The most obvious move was to look within. PhilStage with its connections ithe theater community, took the lead in programming, as headed by Alvin Trono. First to offer her talent was Lisa Macuja-Elizalde of Ballet Manila with her ballet work-out class. Audie Gemora would do a song interpretation workshop. SPIT would do CO-VIDEO, a voyeuristic look at unscripted and unrehearsed scenes. 3rd World Improv, SPIT’s improv school, would do Powerpoint ParTWI, a show of five-minute Powerpoint presentations about anything they could come up with. PETA’s Jack Yabut would do an Asian Movement class. Finally, Rony Fortich would do a work-shop on how to audition properly.

Through Facebook, social media, friends from the press and theater fans, word spread like wildfire – Open House began to roll. Inspired by the cause, performing arts companies and artists started coming out of the woodwork. There was also the challenge of creating material for an online platform. The community started contacting Open House to offer their services as volunteers or to pitch ideas for programs. Open House’s daily time slots (4pm, 7pm and 9pm) quickly filled up.

One of the activities on PhilStage’s wishlist also became a reality. They gathered practitioners from various disciplines for roundtable discussions, notably the all female director panel facilitated by Lexi Schulze.

Open House evolved into, as Toff aptly put it, “a fundraiser that became an avenue for artists to familiarize themselves with a platform that would be the new stage in this new normal.” It was an opportunity to entertain and inspire, to educate practitioners and stake-holders, and more than anything, to provide a sense of community in the theater industry. With donations coming in through Ticket2Me, AWPI was put in charge of distributing the funds since they were the most qualified. Open House also recognized the need to unify and formalize the industry. One step was to make it a prerequisite to be a registered member of AWPI in order to be a beneficiary. This way, more freelancers would be “on the record” so as to avoid “doubling up” on funds received.

Eventually government assistance did start to trickle in. Toff reached out to Liza Diño-Seguerra of the Film Development Council of the Philippines, a sympathetic figure, having been in theater before. FDCP had enacted the DEAR (Disaster Emergency Assistance and Relief) Program to help displaced workers in the audio-visual community, that included performers. Open House applied the DEAR guidelines on who would qualify for benefits. It was a fluid, evolving situation. Open House first focused on the most vulnerable, based on theater shows that were immediately cancelled. FDCP also vowed to match whatever Open House would raise. Liza Diño-Seguerra emphasized that the government “recognizes numbers,” once again bringing to the forefront the need for the creative industry to document its contribution to the GDP.

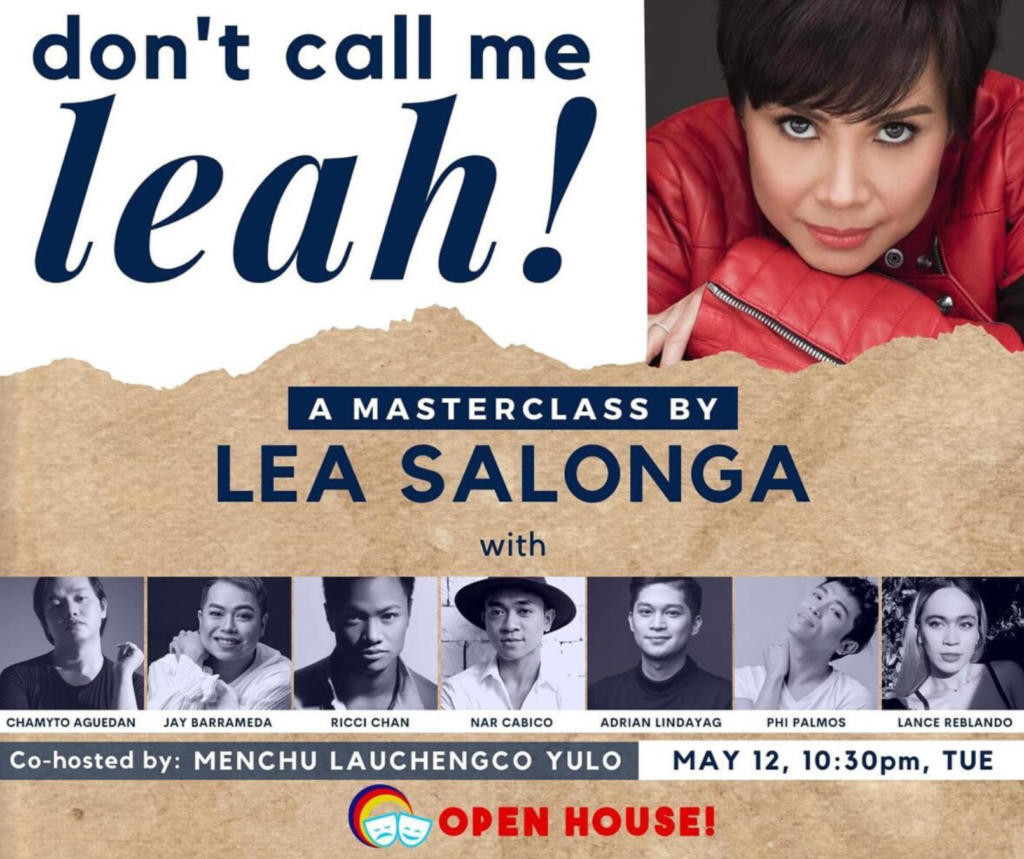

From March 26 to May 15, there were multiple programmings daily, garnering impressive numbers from shows like Blackbox Theater’s Mula Sa Buwan and a rewarding partnership with IWanTV’s Call Me Tita cast, which involved a round-table, script swap and auction to act along with a Tita. Don’t Call Me Leah with the iconic Lea Salonga brought in nearly 150,000 views alone. Missy Maramara was also called out as an MVP, having been involved in twelve productions, eight for SPIT and four for Philstage.*

But Open House’s fundraising could not go on forever. Donor fatigue had begun to set in as the quarantine was extended again and again, and the pandemic raged on. Open House had originally set a goal of P500k but as generous donations came pouring in, they were able to push that goal to P1M. Open House distributed a whopping P1.3M — P2000 relief each for 650 displaced workers. The impact of what was achieved resonated as they read the names of artists involved, and beneficiaries thanked them via video during closing night. Two months later, Open House finally closed with over 100 staff volunteers and 300 artists participating, raising over P2M from donations from fans, practitioners, and other organizations. “We came together as a tribe and community; realized we were talented and selfless in contributing to nation building — this pandemic brought out the best in us,” said Audie.

The future is still uncertain but it is also full of possibilities. As Open House moves on from fundraising, they must now tackle the next phase — sustainability. “There’s a huge crisis but in crisis there is opportunity,” announced Toff. One plan was to learn how to monetize the various streaming platforms. So great was the turnout for Open House that there was actually a lot of unused material. Philstage is planning to present this in the future along with shows from the past that have been recorded. They also want to maintain an Actor’s Fund through AWPI for the next emergency, with an annual or semi-annual fundraiser to keep the coffers filled.

Toff meanwhile found it an exciting time for theater. “Open House can’t end just because quarantine has…we can’t go back to business as usual,” he comments. “This pandemic is an opportunity to rewrite our narrative…there is an irrepressible need to create. It’s called the new normal, not back to normal.” He goes on to say that, having expanded their reach via online, they have hopefully inspired people to appreciate art and theater so as to buy tickets to watch live performances. “Galvanize people to support and give back to the industry,” he exclaims. For Toff, theater must reevaluate its core values in facing the new normal.

As the industry faces many questions, will the audience come back? What new art will emerge as a result? What safety protocols must be implemented to stage a show again? Something had indeed risen out of the efforts of Open House — the National Live Events Coalition of the Philippines. A coming together of all live events’ industries, the NLECPH is working towards substantial wage subsidies to freelancers, stimulus packages, and different kinds of assistance to stakeholders. This is so theater companies will not shut down when there are no live events. Furthermore, it will provide representation to those performing arts industries that have survived on their own. PhilStage would also like to push for a Ministry of Culture and Arts, an office that exists in most Asian countries, but not in the Philippines.

Open House displayed the power of the human spirit within an industry known for making sacrifices for their art. In these uncertain times, Open House provided a venue for a community to come together and provide joy, relief, cooperation and most of all, hope that one need not face the current crisis and the future alone. As the money raised by Open House was distributed, the voices coalesced. They called for changes to an industry whose contributions have largely gone unrecognized by the government, to band and act together. Open House has clearly shown that a new normal also means new opportunities.

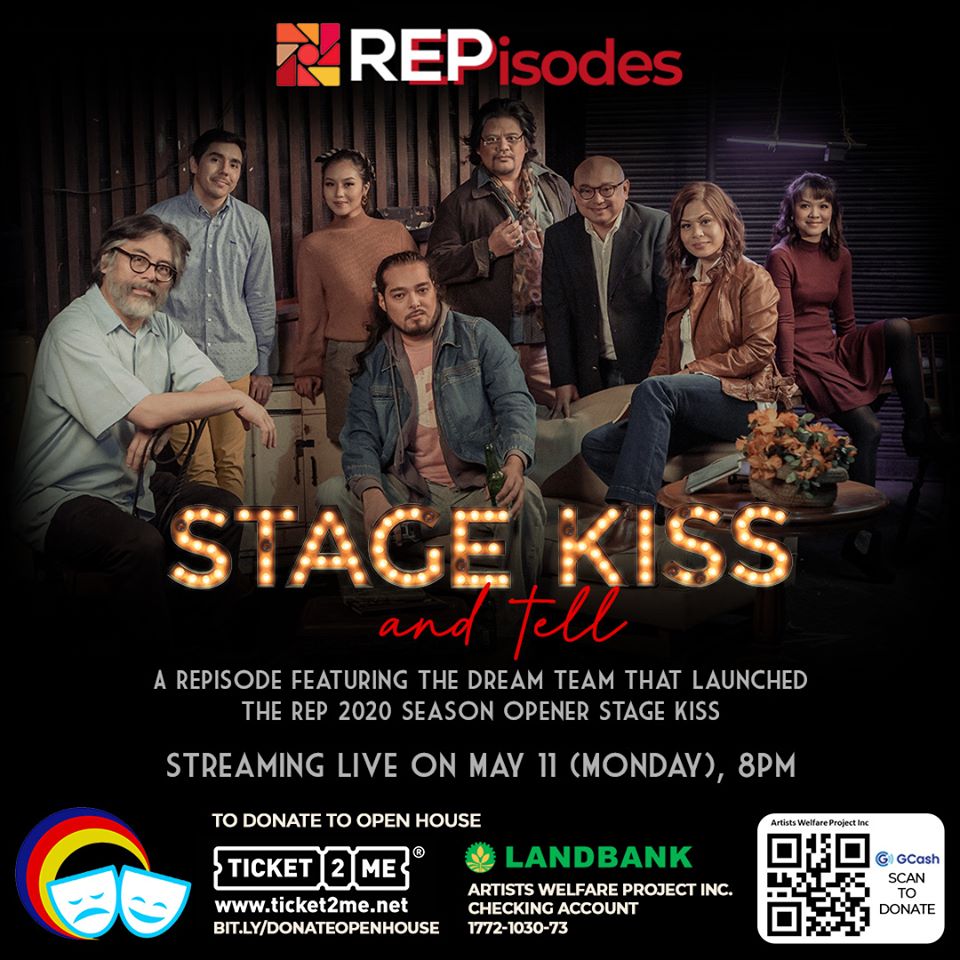

*For its part, REP presented two REPisodes for Open House – A Tea Party with Quarantined Princesses and Stage Kiss and Tell.